Basics of Authentication

In this section, we’re going to focus on the basics of authentication. Specifically, we’re going to create a Ruby server (using Sinatra) that implements the web flow of an application in several different ways.

You can download the complete source code for this project from the platform-samples repo.

Registering your app

First, you’ll need to register your application. Every registered OAuth application is assigned a unique Client ID and Client Secret. The Client Secret should not be shared! That includes checking the string into your repository.

You can fill out every piece of information however you like, except the Authorization callback URL. This is easily the most important piece to setting up your application. It’s the callback URL that GitHub returns the user to after successful authentication.

Since we’re running a regular Sinatra server, the location of the local instance

is set to http://localhost:4567. Let’s fill in the callback URL as http://localhost:4567/callback.

Accepting user authorization

Now, let’s start filling out our simple server. Create a file called server.rb and paste this into it:

require 'sinatra'

require 'rest-client'

require 'json'

CLIENT_ID = ENV['GH_BASIC_CLIENT_ID']

CLIENT_SECRET = ENV['GH_BASIC_SECRET_ID']

get '/' do

erb :index, :locals => {:client_id => CLIENT_ID}

endYour client ID and client secret keys come from your application’s configuration page. You should never, ever store these values in GitHub–or any other public place, for that matter. We recommend storing them as environment variables–which is exactly what we’ve done here.

Next, in views/index.erb, paste this content:

<html>

<head>

</head>

<body>

<p>

Well, hello there!

</p>

<p>

We're going to now talk to the GitHub API. Ready?

<a href="https://github.com/login/oauth/authorize?scope=user:email&client_id=<%= client_id %>">Click here</a> to begin!</a>

</p>

<p>

If that link doesn't work, remember to provide your own <a href="/v3/oauth/#web-application-flow">Client ID</a>!

</p>

</body>

</html>(If you’re unfamiliar with how Sinatra works, we recommend reading the Sinatra guide.)

Also, notice that the URL uses the scope query parameter to define the

scopes requested by the application. For our application, we’re

requesting user:email scope for reading private email addresses.

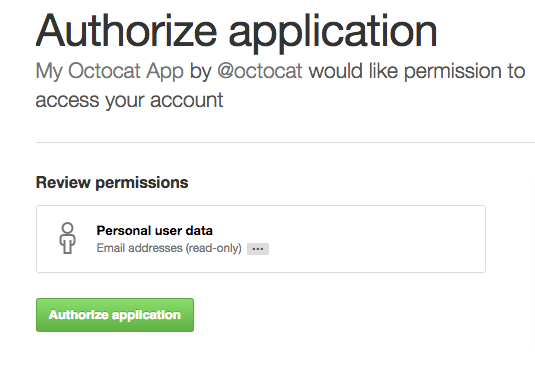

Navigate your browser to http://localhost:4567. After clicking on the link, you

should be taken to GitHub, and presented with a dialog that looks something like this:

If you trust yourself, click Authorize App. Wuh-oh! Sinatra spits out a

404 error. What gives?!

Well, remember when we specified a Callback URL to be callback? We didn’t provide

a route for it, so GitHub doesn’t know where to drop the user after they authorize

the app. Let’s fix that now!

Providing a callback

In server.rb, add a route to specify what the callback should do:

get '/callback' do

# get temporary GitHub code...

session_code = request.env['rack.request.query_hash']['code']

# ... and POST it back to GitHub

result = RestClient.post('https://github.com/login/oauth/access_token',

{:client_id => CLIENT_ID,

:client_secret => CLIENT_SECRET,

:code => session_code},

:accept => :json)

# extract the token and granted scopes

access_token = JSON.parse(result)['access_token']

endAfter a successful app authentication, GitHub provides a temporary code value.

You’ll need to POST this code back to GitHub in exchange for an access_token.

To simplify our GET and POST HTTP requests, we’re using the rest-client.

Note that you’ll probably never access the API through REST. For a more serious

application, you should probably use a library written in the language of your choice.

Checking granted scopes

In the future, users will be able to edit the scopes you requested, and your application might be granted less access than you originally asked for. So, before making any requests with the token, you should check the scopes that were granted for the token by the user.

The scopes that were granted are returned as a part of the response from exchanging a token.

# check if we were granted user:email scope

scopes = JSON.parse(result)['scope'].split(',')

has_user_email_scope = scopes.include? 'user:email'In our application, we’re using scopes.include? to check if we were granted

the user:email scope needed for fetching the authenticated user’s private

email addresses. Had the application asked for other scopes, we would have

checked for those as well.

Also, since there’s a hierarchical relationship between scopes, you should

check that you were granted the lowest level of required scopes. For example,

if the application had asked for user scope, it might have been granted only

user:email scope. In that case, the application wouldn’t have been granted

what it asked for, but the granted scopes would have still been sufficient.

Checking for scopes only before making requests is not enough since it’s posible

that users will change the scopes in between your check and the actual request.

In case that happens, API calls you expected to succeed might fail with a 404

or 401 status, or return a different subset of information.

To help you gracefully handle these situations, all API responses for requests

made with valid tokens also contain an X-OAuth-Scopes header.

This header contains the list of scopes of the token that was used to make the

request. In addition to that, the Authorization API provides an endpoint to

check a token for validity.

Use this information to detect changes in token scopes, and inform your users of

changes in available application functionality.

Making authenticated requests

At last, with this access token, you’ll be able to make authenticated requests as the logged in user:

# fetch user information

auth_result = JSON.parse(RestClient.get('https://api.github.com/user',

{:params => {:access_token => access_token}}))

# if the user authorized it, fetch private emails

if has_user_email_scope

auth_result['private_emails'] =

JSON.parse(RestClient.get('https://api.github.com/user/emails',

{:params => {:access_token => access_token}}))

erb :basic, :locals => auth_resultWe can do whatever we want with our results. In this case, we’ll just dump them straight into basic.erb:

<p>Hello, <%= login %>!</p>

<p>

<% if !email.nil? && !email.empty? %> It looks like your public email address is <%= email %>.

<% else %> It looks like you don't have a public email. That's cool.

<% end %>

</p>

<p>

<% if defined? private_emails %>

With your permission, we were also able to dig up your private email addresses:

<%= private_emails.map{ |private_email_address| private_email_address["email"] }.join(', ') %>

<% else %>

Also, you're a bit secretive about your private email addresses.

<% end %>

</p>Implementing “persistent” authentication

It’d be a pretty bad model if we required users to log into the app every single

time they needed to access the web page. For example, try navigating directly to

http://localhost:4567/basic. You’ll get an error.

What if we could circumvent the entire “click here” process, and just remember that, as long as the user’s logged into GitHub, they should be able to access this application? Hold on to your hat, because that’s exactly what we’re going to do.

Our little server above is rather simple. In order to wedge in some intelligent authentication, we’re going to switch over to using sessions for storing tokens. This will make authentication transparent to the user.

Also, since we’re persisting scopes within the session, we’ll need to

handle cases when the user updates the scopes after we checked them, or revokes

the token. To do that, we’ll use a rescue block and check that the first API

call succeeded, which verifies that the token is still valid. After that, we’ll

check the X-OAuth-Scopes response header to verify that the user hasn’t revoked

the user:email scope.

Create a file called advanced_server.rb, and paste these lines into it:

require 'sinatra'

require 'rest_client'

require 'json'

# !!! DO NOT EVER USE HARD-CODED VALUES IN A REAL APP !!!

# Instead, set and test environment variables, like below

# if ENV['GITHUB_CLIENT_ID'] && ENV['GITHUB_CLIENT_SECRET']

# CLIENT_ID = ENV['GITHUB_CLIENT_ID']

# CLIENT_SECRET = ENV['GITHUB_CLIENT_SECRET']

# end

CLIENT_ID = ENV['GH_BASIC_CLIENT_ID']

CLIENT_SECRET = ENV['GH_BASIC_SECRET_ID']

use Rack::Session::Pool, :cookie_only => false

def authenticated?

session[:access_token]

end

def authenticate!

erb :index, :locals => {:client_id => CLIENT_ID}

end

get '/' do

if !authenticated?

authenticate!

else

access_token = session[:access_token]

scopes = []

begin

auth_result = RestClient.get('https://api.github.com/user',

{:params => {:access_token => access_token},

:accept => :json})

rescue => e

# request didn't succeed because the token was revoked so we

# invalidate the token stored in the session and render the

# index page so that the user can start the OAuth flow again

session[:access_token] = nil

return authenticate!

end

# the request succeeded, so we check the list of current scopes

if auth_result.headers.include? :x_oauth_scopes

scopes = auth_result.headers[:x_oauth_scopes].split(', ')

end

auth_result = JSON.parse(auth_result)

if scopes.include? 'user:email'

auth_result['private_emails'] =

JSON.parse(RestClient.get('https://api.github.com/user/emails',

{:params => {:access_token => access_token},

:accept => :json}))

end

erb :advanced, :locals => auth_result

end

end

get '/callback' do

session_code = request.env['rack.request.query_hash']['code']

result = RestClient.post('https://github.com/login/oauth/access_token',

{:client_id => CLIENT_ID,

:client_secret => CLIENT_SECRET,

:code => session_code},

:accept => :json)

session[:access_token] = JSON.parse(result)['access_token']

redirect '/'

endMuch of the code should look familiar. For example, we’re still using RestClient.get

to call out to the GitHub API, and we’re still passing our results to be rendered

in an ERB template (this time, it’s called advanced.erb).

Also, we now have the authenticated? method which checks if the user is already

authenticated. If not, the authenticate! method is called, which performs the

OAuth flow and updates the session with the granted token and scopes.

Next, create a file in views called advanced.erb, and paste this markup into it:

<html>

<head>

</head>

<body>

<p>Well, well, well, <%= login %>!</p>

<p>

<% if !email.empty? %> It looks like your public email address is <%= email %>.

<% else %> It looks like you don't have a public email. That's cool.

<% end %>

</p>

<p>

<% if defined? private_emails %>

With your permission, we were also able to dig up your private email addresses:

<%= private_emails.map{ |private_email_address| private_email_address["email"] }.join(', ') %>

<% else %>

Also, you're a bit secretive about your private email addresses.

<% end %>

</p>

</body>

</html>From the command line, call ruby advanced_server.rb, which starts up your

server on port 4567 – the same port we used when we had a simple Sinatra app.

When you navigate to http://localhost:4567, the app calls authenticate!

which redirects you to /callback. /callback then sends us back to /,

and since we’ve been authenticated, renders advanced.erb.

We could completely simplify this roundtrip routing by simply changing our callback

URL in GitHub to /. But, since both server.rb and advanced.rb are relying on

the same callback URL, we’ve got to do a little bit of wonkiness to make it work.

Also, if we had never authorized this application to access our GitHub data, we would’ve seen the same confirmation dialog from earlier pop-up and warn us.

If you’d like, you can play around with yet another Sinatra-GitHub auth example available as a separate project.